Gameworkers and Guildworkers,

I started thinking about game workers and guild workers last year. I was in Central Europe Time, procrastinating and jetlagged, so I followed the burning images of Notre Dame cathedral for several 24 hour news cycles. I was in the middle of a month of touring the mobile game GIGCO: Escape the Gig Economy; a version of my MFA thesis I’d developed the year before. It’s a video game about gig workers, but I was really shopping around my grad student galaxy brain by which I insisted video games were the media du jour for analyzing contemporary labour relations.

So I fixated on #NotreDameFire as the posts shifted from images of the still-burning cathedral to screen captures of a AAA video game from five years earlier. Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed Unity had featured a highly detailed model of the Notre Dame cathedral that played a key role in the game’s narrative. The model had been created by a sole developer, and was now being circulated as potential reference material for the restoration of the cathedral.

Image source: Hatfield, Damon, and Jonathon Dornboogie. "How Assassin's Creed Could Help Rebuild Notre Dame." IGN. YouTube video, 0:01:30. Posted 16 April 2019.

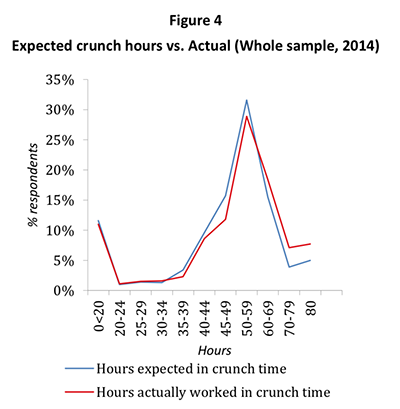

Of course, the 500,000 Euro Ubisoft gave to the restoration effort was likely to be more help than the gamified virtual model. But the ensuing juxtaposition of the two cathedrals on social media caught my attention. Both had been built by workers using new technologies, albeit in two distinct societies. I’d been drawn to Gothic architecture by left leaning art critics; both John Ruskin and William Morris referred to Gothic’s worker-lead model to criticize their contemporary Neo-Gothic industrialists churning ornament out of the smokestacks of Victorian London. Meanwhile the notorious working conditions of the game industry had been a hot topic in the past year, with its workers whose hours[1] often matched the numbers spent by Victorian factory labourers prior to their socialist victories of the 8-hour workday.[2] Was it possible that the Medieval craftspeople who built Notre Dame cathedral had better working conditions than those pushing pixels in the industry which built the virtual recreation?

The project began with research. It was relatively easy to find the documents which outlined the rights and regulations of the associations of workers who built the cathedral, due to the prominence of ‘masons’ in conspiracy theories.[3] Etienne Boileau’s Livre Des Métiers, a collection of statutes submitted by the Guilds of Paris in the middle of the 13th century chronicled the expected working conditions for over 100 trades. The masons, plasterers, wood- and stoneworkers were all covered under the header for building-related trades.[4] These workers had a maximum number of hours they could work in a week,[5] and their professional associations would provide cash and in-kind support in the cases that building projects were cancelled or seasonally closed.[6] Game Workers Unite, the leading grassroots organization fighting for the unionization of the industry since 2018, cites crunch (overtime) and job insecurity as two of the industry’s core problems for its workers.[7] In terms of working conditions, the Parisian Guilds of the building trades had greater industry protections than game workers.

Image source: Weststar, Johanna, and Marie-Josée Legault. “Developer Satisfaction Survey.” International Game Developers Association, 2015.

To compare the state of tech industry workers to those working in plague-frequented Medieval Europe is a slight in itself, and possibly controversial. What does it mean to compare industry protections to a pre-industrial era? But the interpretation of history has always been controversial, and rarely on the side of the workers. While it’s problematic to romanticize the Medieval Guild structure as Ruskin and Morris would, they were working against the historiography of guilds which insisted such worker organizations were corrupt, rent-seeking, or elite institutions.[8] Guilds were communal organizations being studied in the Enlightenment’s era of the Individual. Hobbes, Locke, Hegel, Adam Smith, Karl Marx: all had their interpretations of the guilds.[9] While it may be inaccurate to consider the guilds as proto-unions, the statutes they produced for Paris’ Livre Des Métiers were informed by workers of the trades and not assigned by the emerging state bureaucracy. The practices developed by the professional associations (prior to their legally recognized status as guilds post-Livre Des Métiers) enabled the specialized knowledge of the trade to be transmitted and innovated despite the lack of a modern state bureaucracy or education system.[10]

Workers who use or develop new technologies through their work are often vulnerable under contemporary labour laws overseen by the government. The language of the gig economy has skirted labour regulation by labelling their workers as contractors rather than employees. Canada’s provincial labour laws, which cover workers without unions, leave loopholes for exploitation through their ‘tech worker exemptions.’[11]

As my research focuses on game workers, who notoriously fall prey to exploitative working conditions that are enabled by inadequate government law and the lack of any organization at the industry level, I will be equating the Parisian guilds’ statutes to industry protections that might be found in the modern equivalent of a union. This analogy is reinforced by my findings in the Guild statutes which contain regulations against some of the core issues that the Game Workers Unite organization is fighting, specifically, crunch time, working hours, layoffs, and job security.

Image source: "Resouces: GWU Literature." Game Workers Unite. www.gameworkersunite.org/

GWU also identifies racism, sexism, and transphobia within the industry as key motivators for a change in the system. Whether it materializes through systemic or individual behaviour, the oppression of marginalized identities in the games industry is one of issues that the general public is most aware of. I firmly believe in GWU’s mission to empower all workers, but this will be where my analogy ends. I don’t believe my research can do any adequate comparison between guild workers on topics of identity as it is understood in the modern era, and I think it would be bad scholarship to try so. Such identities are products of modern relationships between liberal states and their citizens; as Judith Butler identifies, “identities are formed within contemporary political arrangements in relation to certain requirements of the liberal state.”[12] These identities and their discourse rely on legal relationships that did not exist in 13th century Paris. However, my research into the guild system of this region and era has granted information about medieval gender roles, immigrant and transient labour, and the free association of working people who fell under these categories. I will be dedicating significant time into exploring how these workers negotiated the roles Medieval society gave them.

Finally, I’d like to address that Ubisoft, the publisher of the Assassins’ Creed Unity and owner of the virtual Notre Dame cathedral, is widely accepted as a good company for its workers. Speaking to folks who have worked for the Canadian studios of the company, jobs at Ubisoft are relatively secure and employees aren’t exposed to the harsh crunch conditions prevalent in other AAA game studios. This project isn’t about a studio, it’s about a system; whether an industry should aspire to work for a benevolent overlord or redistribute the power amongst the workers, without whose brains and muscle not a single wheel would turn.

________________

[1] Weststar, Johanna, and Marie-Josée Legault. “Developer Satisfaction Survey.” International Game Developers Association, 2015.

[2] Based on 69-hour work week, Woytinsky, W. S. "Hours of Labor". Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. III. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1935.

[3] I came across an unofficial english translation of Livre Des Métiers through a Google-search directed link to a web 1.0 page about freemasons and the illuminati. I’ve since made do with the 19th century official reprinting and Google Translate.

[4] See Titre XLVIII, Boileau, Étienne. Le Livre Des Métiers. Paris, France: Imprimerie Nationale, 1879, 88.

[5] Ibid., 88.

[6] Rosser, Gervase. "Crafts, guilds and the negotiation of work in the medieval town." Past & Present 154 (1997): 3-31.

[7] “What Can Unions Do to Help?” Game Workers Unite, March 2019, 6–14.

[8] Epstein, Stephan R., and Maarten Prak, eds. Guilds, innovation and the European economy, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press, 2008, 1.

[9] Rosser, Gervase. The art of solidarity in the middle ages: guilds in England 1250-1550. OUP Oxford, 2015, 10.

[10] Epstein, Stephan R., and Maarten Prak, eds. Guilds, 1.

[11] This loophole interprets the definition of a tech worker as workers using technology such as computers in their work, which companies cite to avoid paying overtime to their employees. As many industries have integrated computers into their workplace, this loophole should be a concern for the broader public. “Exclusions, High Technology Companies - Regulation Part 7, Section 37.8.” British Columbia Employment Standards Guide. Province of British Columbia. Accessed March 30, 2020.

[12] Butler, Judith. The psychic life of power: Theories in subjection. Stanford University Press, 1997, 100.

Get Gameworkers and Guildworkers

Gameworkers and Guildworkers

Those who fight for those who work for those who play

| Status | Released |

| Author | SpekWork |

| Tags | artgame, Experimental, game-essay, Unity |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Subtitles |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.